Geography: n. the study of the physical features of the earth and its atmosphere, and of human activity as it affects and is affected by these, including the distribution of populations and resources, land use, and industries.

Etymology: geo- “earth” + -graphia “description, writing”

Key Terms and Concepts

Physical geography:

- earth (ground, roots, cover, sprout, dead, desert), water (rivers, sailing, fishing, drowning, pearls (tempest decay), specific rivers, soda water) fire (flames, burning, infernal, smoke, light or dark, fire as heat, unlit), air (wind, fog, sighs, exhaling, odours, synthetic perfumes, enclosure, interior space, home), urban landscape (crowds, sound of horns and motors, human artifacts littered)

Metaphorical geography:

- the interplay between human, nature, urbanity, and modernity; linguistic space within the poetic form

When a person says “geography,” most people just imagine various landscapes, topography, and physical features. In its definition and in the root of “geography” itself, it’s really the documentation of the physical, the intricacies and elements of a landscape, and human interaction in the natural world that describe the heart of its meaning. Under this widely scoped definition, we want to acknowledge that our evidence and analysis is in no way comprehensive of all geographical motifs within The Waste Land, but only represents a selection of what might entail geography in the text. Thus, we primarily focused on the four main natural elements that constitute the earthly geography – Earth, Water, Air, and Fire, how they interact with each other, and how humans and nature interact.

Earth

The first section of TWL, Burial of the Dead, explicitly evokes the motif of earth as a site of burial and rebirth. These images reverberate throughout the later sections. We could categorize these images pertaining to earth into two archetypes:

- Barren, arid land of dust or rock lacking water:

- “Stony rubbish,” “shadow under this red rock”

- “A heap of broken images, where the sun beats, / And the dead tree gives no shelter, the cricket no relief, / And the dry stone no sound of water”

- “I will show you fear in a handful of dust”

- Belladonna, the Lady of the Rocks / The Lady of situations

- “Yet there the nightingale / filled all the desert with inviolable voice”

In the first section, images of earth lacking water, a sign of fertility, were evoked repeatedly.

- Damp or wet land with presences of water:

- “Breeding / Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing / memory and desire, stirring / dull roots with spring rain”, “covering / Earth in forgetful snow”

- “That corpse you planted last year in your garden, / Has it begun to sprout? Will it bloom this year?”

- “Yet when we came back, late, from the hyacinth garden, / Your arms full, and your hair wet”

- “The wet bank”, “the brown land”

- “A rat crept softly through the vegetation / Dragging its slimy belly on the bank”

- White bodies naked on the low damp ground

In this series of images, there is an implicit interplay between water and the earthly landscape. Whether it was the gardenic images or the swampy scenes, the consistently bleak and sometimes ironic outlook of Eliot’s vindicates water’s failure to fertilize, but instead almost in a sense that the land was violated by water. When crept on by traces of water, land seems to be further cursed rather than fertilized, for example, in the gardens, where its symbolism of life was subverted under an overwhelming presence of death; and at the river banks, or moss-laden land, where water infiltrates earth with an undesirable condition of life that desires death as a promising end.

Phlebas the Pheonician and his bones were also a thread that connected the water and the earth imagery. From “I think we are rats’ alley / where the dead men lost their bones,” “bones cast in a little low dry garrett, / Rattled by the rat’s foot only,” to finally “A current under sea / Picked his bones in whispers,” Phlebas first surrenders his bones from his body to the land, yet it was finally in the waters where the current helps him recollect the scattered bones.

Fire

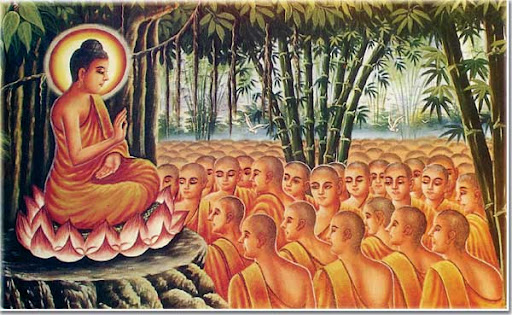

The Fire Sermon is named after the Buddha’s “Fire Sermon Discourse” which preaches that salvation is only accessible to those who disconnect themselves from the senses and human emotions. In TWL, the beginning of the section is characterized by a contradictory lack of warmth: “by the waters of Leman I sat down and wept” (182), “Sweet Thames” (176) and “cold blast” (185). Fire is absent in the first stanza, and even in the rape scene near the end of the section, the typist is cold and unmoved. Only the clerk appears to be animated with the “burning” mundane emotions that, according to the Discourse, clouds humans’ perception of reality and prevents one from achieving “liberation from suffering.” In TWL the clerk is, in some manner, “blinded” by his passions — in this sense, he is Tiresias’s foil because the blind Tiresias, who is quite literally detached from his senses, is able to see the “true” events that will occur in the future. At the same time, Tiresias wished to die, contradicting the Buddha’s sermon that “liberation from suffering” means detachment from the mundane senses. In TWL, “liberation from suffering” means death, and fire in this context is a motif for life — simultaneously as a punishment, distortion of reality, and self-destruction.

Water

Eliot leaves no rock unturned exploring the multi-faceted (and often contradictory) nature of water: it can have a positive connotation as a symbol of revival (April’s spring rains in the opening lines and the dryness of death,) or, more commonly with Eliot (though Keeliah notes this is typically untraditional), Eliot portrays water in scenes of destruction and suicide to subvert reader expectations in a Modernist fashion. Be it drowning or drought, water appears primarily with a negative connotation: (“And the dry stone no sound of water.” (24), “Fear death by water,” (50), From Ritual to Romance drought/infertility catalyzing a wasteland, “Oed’ und leer das Meer,” (42) empty and desolate as the sea (Tristan and Isolde), the drowned Phoeneician Sailor transforming from person to cadaver with pearls, Baudelaire “A headless cadaver pours out, like a river,”Laertes from Hamlet reflecting on Ophelia’s suicide by drowning “Too much of water hast thou, poor Ophelia, /And therefore I forbid my tears”). Even Eliot himself acknowledges that these references can all serve as one and start to blend together (see his note on line 218), but his use of water shows more than just blunt devastation: “By the waters of Leman I sat down and wept . . . / Sweet Thames, run softly till I end my song, / Sweet Thames, run softly, for I speak not loud or long,” (175). At the beginning of the fire section, the river permeates through multiple stanzas and here, water appears not only as a theme, but guides the repetitive structure of the lines in the same way a river rushes over a brook.

Air

Wind is a recurring motif in TWL, appearing first as a “noise… under the door” (lines 118-19) in A Game of Chess. In The Fire Sermon, the wind loses its voice, “crosses the brown land, unheard” (174). In Death by Water, the sailor looks “windward” (320) like Phlebas the Phoenician. The wind is personified as something whispering, giving direction. The wind seems to accompany the barrenness of the waste land.

- Water as a destructive force and site of suicide

- Huge sea-wood fed with copper / Burned green and orange, framed by the coloured stone, / In which sad light a carvéd dolphin swam.

- “Oed’ und leer das Meer.” an open body of water

- By the waters of Leman I sat down and wept . . . / Sweet Thames, run softly till I end my song, / Sweet Thames, run softly, for I speak not loud or long.

- Rushing structure like a river, but also thematically related to water

- “This music crept by me upon the waters” 257

- Homeward, and brings the sailor home from sea, / The typist home at teatime 221-22

- **also segways nicely into air, can extend to human presence as well

- “They wash their feet in soda water”

- “sea-wood” and “dolphin,” she is “troubled, confused / And drowned”

- “While I was fishing in the dull canal” 189

- Where fishmen lounge at noon: where the walls / Of Magnus Martyr hold

- The Grail

- V. What the Thunder Said

- Sibyl: enclosure

- Interior space

- Under the brown fog of a winter dawn..Sighs, short and infrequent, were exhaled —- “The wind / Crossed the brown land, unheard.”

- Fresh the wind blows towards home: my Irish child, where are you now?

- ‘What is that noise?’

- The wind under the door.

- ‘What is that noise now? What is the wind doing?’

- Nothing again nothing.

- “Well, that Sunday Albert was home,” – the private v. public sphere

- Unstoppered, lurked her strange synthetic perfumes, / Unguent, powdered, or liquid—troubled, confused / And drowned the sense in odours; stirred by the air

- Artificial quality of Phiolmela’s home (and so many others, e.g. Cleopatra) juxtaposed with the typist’s home

- Female interior space

- Well, that Sunday Albert was home, they had a hot gammon,

Wind is a recurring motif in TWL, appearing first as a “noise… under the door” (lines 118-19) in A Game of Chess. In The Fire Sermon, the wind loses its voice, “crosses the brown land, unheard” (174). In Death by Water, the sailor looks “windward” (320) like Phlebas the Phoenician. The wind is personified as something whispering, giving direction. The wind seems to accompany the barrenness of the waste land

The Urban Landscape and Human Presence in the Geography

While the wasteland is enhanced by and further degraded by natural elements, Eliot incorporates hints of how urbanity impacts the landscape through descriptions of industrialization, crowds, and human objects.

Following the horrors of World War I, a developmental period of modern industrial societies and a rapid growth of cities likely influenced Eliot’s representation of human geography. Sound, often associated with machinery, appears in The Wasteland just twice: “But at my back from time to time I hear / The sound of horns and motors” (195-196) and later

“If there were the sound of water only” “But there is no water” (353, 359). This subtle influence of sound/industrialization hints at our displacement of natural resources, but the description of the Sweet Thames declares human presence in a way that almost imbues life (albeit perhaps a life of waste) into the water: “Sweet Thames, run softly, till I end my song. / The river bears no empty bottles, sandwich papers, / Silk handkerchiefs, cardboard boxes, cigarette ends / Or other testimony of summer nights.” (175-178)

This human contribution to the river is juxtaposed when Eliot borrows Baudelaire’s descriptions of the woman’s possessions, sexual violence, and death, and makes an intratextual allusion to Madame Sosostris, Eliot describes “The glitter of her jewels rose to meet it, / From satin cases poured in rich profusion; / In vials of ivory and coloured glass / Unstoppered, lurked her strange synthetic perfumes, / Unguent, powdered, or liquid—troubled, confused / And drowned the sense in odours” (84-89) The wording of “lurked,” “synthetic,” “troubled, confused,” and “drowned” emphasize the underlying negative view of humans (and perhaps women in particular), portraying humans as the most contrived part of the wasteland, overstepping bounds into the natural world and thus bleeding into natural consequences.

The artificial human elements are juxtaposed with the natural, even to the point where Eliot calls into question the liveliness of the people he describes: the“Unreal,” and “Unreal City,” in particular is mentioned three times (60, 207, 377), filled with “crowds”: “I see crowds of people, walking round in a ring” (56) and the “crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many, / I had not thought death had undone so many” (62). In Eliot’s note for line 46, he mentions “also the ‘crowds of people’, and Death by Water is executed in Part IV,” leaving readers wondering the timeframe of death for these humans and what really counts as being dead. Calling these people into question also made us wonder if Eliot would have viewed the woman described in A Game of Chess any more alive than the crowd flowing over the bridge.