Sensation

Eliot’s generous use of reference sources to write The Waste Land provides a wealth of information and context for the text, such that the connections between the sources are important to understanding the poem. Many of the sources deal with the concept of sensation, including the five senses, but also go beyond the physical to deal with the spiritual or intangible. The most important sense to appear in The Waste Land is sight, whether physical or spiritual.

Sight is connected with desire: it allows us to see things, therefore giving us the ability to desire them. Sight also provides a medium to confirm reality, or conversely to dismiss reality that isn’t wanted or recognized. The sensation of sight is used to deeply express sexual or material desire, and conversely the choice of neutrality and apathy. Eliot’s inclusion of the story of Tiresias serves as an excellent departure point for further exploration of sight in the poem.

Throughout many of the referenced texts, there is a clearly defined separation between the physical and spiritual body and senses, most clearly demonstrated in Eliot’s description of Tiresias: “I Tiresias, though blind, throbbing between two lives,/Old man with wrinkled female breasts, can see.” (Eliot, line 218-219) There are multiple versions of Tiresias’ story; one involves his accidental viewing of Minerva at her bath, for which he is punished with blindness. The alternate version of the story is that Jove and Juno ask Tiresias to settle a disagreement about whether men or women experience more pleasure during sex; Tiresias agrees with Jove, saying that women have a more pleasurable experience, so is cursed with blindness by Juno. In both versions, Tiresias is simultaneously cursed with physical blindness but blessed with prophetic sight, establishing that the physical and spiritual self and senses are totally separate.

Tiresias Strikes at the Snakes

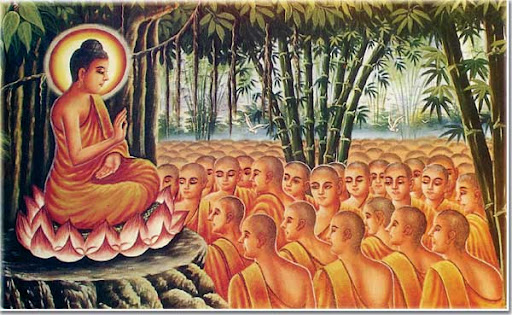

Eliot builds upon the idea of a separate physical and spiritual body through his inclusion of Augustine’s Confessions and “The Sermon on the Mount” from the Gospel of Matthew. In his Confessions, Augustine writes “These seductions of the eyes I resist, lest my feet wherewith I walk upon Thy way be ensnared; and I lift up mine invisible eyes to Thee, that Thou wouldest pluck my feet out of the snare.” (Augustine, Confessions) The “snare” Augustine makes reference to is sin, and his “invisible eyes” seem to be a reference to his spiritual gaze. The argument here is that physical sight leads to sin, an argument which is built off of in “The Sermon on the Mount.” In the “Sermon,” the eyes are described as the cause for good or evil in a person: “The light of the body is the eye: if therefore thine eye be single, thy whole body shall be full of light. But if thine eye be evil, thy whole body shall be full of darkness. If therefore the light that is in thee be darkness, how great is that darkness!” (Matt., 6.22-23) In both of these sources, physical sight is presented as the cause for sinful behavior. The idea of sight as a precursor to sin is echoed in an entirely different religious tradition which Eliot also cites. In the Fire Sermon Discourse from the Pali Canon, the Buddha delivers a sort of sermon to a group of disciples, stating that

“the learned and noble disciple conceives an aversion for the eye, conceived an aversion for forms, conceives an aversion for eye-consciousness, conceives an aversion for the impressions received by the eye; and whatever sensation, pleasant, unpleasant, or indifferent, originates in dependence on impressions received by the eye, for that also he conceives an aversion.” (Warren, 352)

The choice of the word “aversion” illuminates the strength of physical sight: rather than working to develop an indifference or neutrality towards things perceived with the eye, a “learned and noble disciple” must develop an intense dislike towards the sight.

Buddha Delivers the Fire Sermon

Eliot seems to agree not only with the concept of separate physical and spiritual body, but also with the idea of sight leading to sin based upon some of the other stories he chooses to include. He references the story of Tereus and Philomena, in which Tereus is so filled with lust at seeing Philomena that he brutally rapes her; the story of Tristan and Isolde, often hailed as one of the greatest love stories ever, but which begins with Tristan’s deceiving Isolde into falling in love with him; the story of once beautiful Sybil, in which she is cursed to near eternal life for refusing Apollo’s lust. In each of these examples, a man’s sight leads him to desire, to lust, causing him to sin, irrecoverably altering a woman’s life.

Procne, Philomela, and Tereus |  Tristan and Isolde |  Apollo and Cumaen Sybil |

Eliot’s explicit reference to the aforementioned sources establishes a connection between them; based upon the sources he presents, he seems to believe that the physical and spiritual body are separate, and that the physical sight can lead only to sin and harm, whereas the spiritual sight helps one to attain enlightenment.

Tiresias and Sight:

The figure of Tiresias and his description within the poem uses sight, or the lack thereof, in a complex critique of human perception and apathy. Upon witnessing the scene in “The Fire Sermon,” Tiresias relates:

“I Tiresias, though blind, throbbing between two lives, Old man with wrinkled female breasts, can see… I Tiresias, an old man with wrinkled dugs / Perceived the scene, and foretold the rest—” … Tiresias then watches the scene unfold, until finally, the man “bestows one final patronising kiss, / And gropes his way, finding the stairs unlit . . .”

Despite Tiresias’s blindness, he is still forced to bear witness to the scene of the female typist in “The Fire Sermon.” Tiresias’s lack of sight is conjoined with his perception, to appeal to the reader’s perception of the scene equally. Tiresias sees everything, but on account of his blindness will say nothing, even as the woman in the poem refuses to react or protest: both are possibly used by Eliot as a commentary on human perception and indifference. Tiresias, with his foresight, should be most involved and passionate for the well being of others; instead, he is the embodiment of passivity and meaningless vision. The end of the scene appeals in a different way to the sensation of sight: the young man gropes his way in the darkness, “finding the stairs unlit.” These fleeting sentiments appeal beyond descriptive language to the sensation of blindness that can be imagined and shared by the reader beyond any eloquent description. Eliot opts to appeal to the common humanity of sight in his communication with the reader.